One day, Londoners emerged from the Brent Cross tube station—a weathered concrete-and-stone facade in a mixed residential-commercial neighborhood in London’s Barnet borough—to discover, wrapped around a bike lane sign, a canary yellow sign making a series of left and right turns in a zig-zag shape. Or perhaps they walked down the street and saw a long sign in the same bright color emerging straight from the ground and hooking left. Or they looked up and saw, attached to a streetlight, another serpentine sign wrapping in a loop-the-loop.

and founder of Fieldwork Facility

© Megan Barclay

But these attention-grabbing signs are whimsical for a reason: the shapes mirror the turns and twists the pedestrians would have to follow to get to Brent Cross Station, a new mixed-use commerce, sports and recreational development by the Barnet Council and real estate company Related Argent. And this wayfinding system that has transformed the Brent Cross neighborhood—and many neighborhood-revitalization projects to come, like commissioning public art and creating “design interventions” for storefronts all throughout the area—come from the imaginations at Fieldwork Facility, a small design studio with a predilection for tackling big design challenges.

Browse Projects

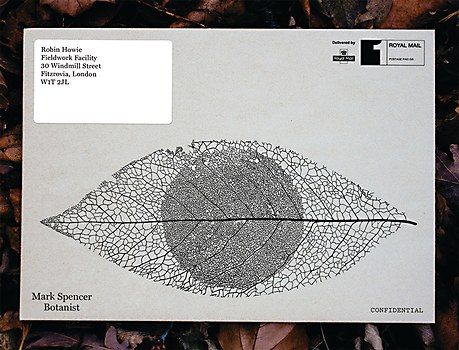

Nestled in London’s Hackney borough in a shared creative space, the studio comprises founder and creative director Robin Howie and a growing team of freelancers. “I describe Fieldwork Facility as a design studio for uncharted territories,” Howie says. “Really, this is a fancy way of saying that we enjoy working on unusual design challenges.”

Established in 2010, Fieldwork Facility began right as Howie graduated from the Royal College of Art—the day after he had his degree show. “Starting the studio right out of college was a naive move, but perhaps naive in a wonderful sense,” Howie says. During his degree course, he worked on two briefs: one for artist and curator Jean Matthee, and another for the R&D department of UK Sport, the government agency promoting excellence in sport—including at the Olympic and Paralympic Games. Titled Monuments, the project involved designing graphics for Team GB’s skeleton sled squad at the 2010 Olympic Winter Games in Vancouver. Howie created portraits with 3-D-mapping scanners of every athlete on the team and had these graphics printed on their individual sleds.

“Both [Monuments and my work for Matthee] went really well, and it was mentioned that, at some time in the following year after I graduated, there could be a couple more projects I could also work on,” Howie recalls. “I just thought if I had those projects coming up and could fill in the gaps [with other work], then I had a studio. Like I say, [establishing Fieldwork Facility] was wonderfully naive but still enough to carry me forward on the journey I had set out on.”

Both clients returned to work with Howie again: this time, Matthee invited him to work with her on a series of keynote lectures at the Tate Gallery with the theme of topology, with speakers like Olafur Eliasson and Ernesto Neto, and UK Sport commissioned him to design the gear for Team GB’s cycling team—cycling being Howie’s favorite sport—at the 2012 Olympic Summer Games in London. Unfortunately, both projects didn’t turn out as he’d hoped.

“A couple of months before the games, Team GB’s main kit sponsor got wind of our project, and let’s just say they weren’t too enamored that an unknown designer was working on highly visible elements of [the] kit,” Howie explains. “After a fantastic experience of meeting Olympians, following World Cup race meets and hanging out with secret squirrels in wind tunnels, the project was canceled.

“The Tate project did happen, however, though with a much smaller scope,” Howie continues. Initially, he’d hoped to be responsible for the design collateral and participate in the experiential design of the Tate lectures with the added challenge of interactivity. “Still a lovely opportunity, but a good-sense check for [my] wonderful naivety,” he says.

Despite these disappointments, Howie credits these projects for setting his studio in motion. “I was working incredibly hard to seek out other brave clients that might take a punt on me,” he recalls, “and it certainly helped being a resourceful designer while we emerged from a huge recession. I managed to find other work between the gaps in those projects and just carried on.”

The only setback facing Howie then was deciding on a name for his studio. “It had definitely been an ongoing anxiety that I had an unnamed design studio,” he admits, “but a new project required me to have a proper business bank account, and you can’t open a business bank account without a business name, so I needed one pretty quick.” Luckily for him, the studio’s ethos had already taken root, and he knew he wanted a name that would reference it. “I wanted a name that felt authoritative and empowering, but also a bit ‘off-balance’ and independently minded—not an easy brief!” Howie says. “Fieldwork was on the table for a long time, but as lovely and direct as it was, other Fieldworks exist across the globe. Adding Facility seemed to activate the name in a way that resonated with how we work.”

The same design ethos has carried throughout Fieldwork Facility’s work: the idea of “design as a role of citizenship.” When I ask about what this means to Howie, he explains that before designers are designers, they are citizens. “To be a citizen doesn’t require anything from you: all you have to do to be a citizen is to live somewhere,” he says. “Citizenship, for me, is a much more interesting concept because it implies [you are] proactive and participate in the multiple communities you reside in. ‘Design is a role of citizenship’ is all about the responsibility to add civic value [to your projects] and aim to do good.”

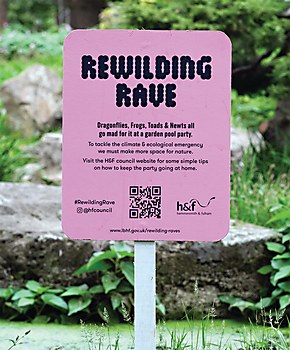

As an example, Howie points to Rewilding Raves, a 2022 project for the climate emergency department of the London Borough of Hammersmith & Fulham Council. “[The client’s] brief to us was, really: Can you make a campaign to encourage people to do more gardening?” Howie recalls. “But we read between the lines and reframed it as a design challenge: How might we foster more nature and biodiversity in our private and shared spaces?” Leveraging the knowledge that younger generations were taking up gardening during the pandemic and that music fans are more likely to make ecofriendly lifestyle changes, Fieldwork Facility created a combination print-and-experiential campaign involving OOH ads and signage in natural spaces—some featuring holes in their stands that doubled as bee hotels for solitary bees. Both featured QR codes linking to the council’s webpage, where people could find tips on how to encourage biodiversity around their homes.

“At first sight, the Rewilding Raves campaign appears to be for a music festival or a club night,” Howie explains. “It invites the borough to make pool parties for dragonflies and frogs or wildflower habitats where butterflies and bees can lose their inhibitions. We wanted to avoid the typical doom-laden messaging around the climate emergency and instead encourage people to feel great about participating in their neighborhoods becoming greener, wilder places.”

Additionally, Fieldwork Facility ran a social media campaign with hyperlocal context to suggest specific ways communities could help restore nature. “For example, the borough doesn’t have enough naturally occurring wet spaces,” Howie says, “but the ponds it does have are really thriving. So, to create more of a network of wet spaces, we triangulated the main ponds and targeted nearby garden owners, encouraging them to add a mini pool party for frogs, dragonflies and newts.”

These multimedia design projects with multifaceted elements seem to be the trend in Fieldwork Facility’s output. On how he arrives at these executions, Howie divulges two key points. The first: Fieldwork Facility is a design firm that defies specialization. “I absolutely love the breadth of our output,” Howie says. “Sure, it does make clear business sense to specialize, but I think by sticking to our guns, I’ve carved out this lovely position to be specialists in not specializing. I thrive on this diversity of output; I love that, within a year, we will be working on campaigns, brands, exhibitions, experiences, film titles or furniture, among other things.”

The other key point is a creative equation: idealism × pragmatism + poetry = relentless optimism. “This is a little theory I’ve been testing out lately,” Howie says. “To approach the world’s most pressing challenges, we need relentless optimism that change can happen. We start with an idealistic point of view, a vision for the change our clients want to see in the world. But idealism isn’t enough; things like climate change don’t course correct just because we want them to. So, we multiply our idealism with pragmatism, which is essentially using strategy for how to bring that idealistic vision to life. Being pragmatic doesn’t win hearts and minds, which is why we need poetry—the creative execution—to make that initial vision sticky and actionable.”

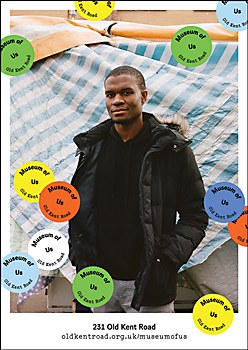

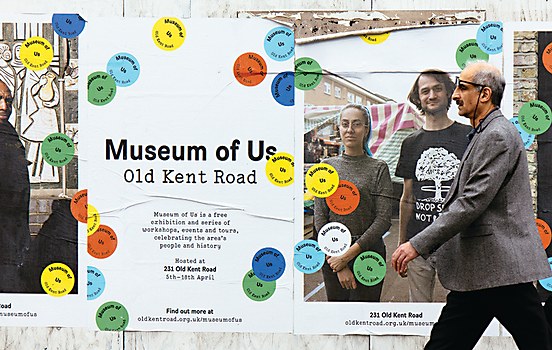

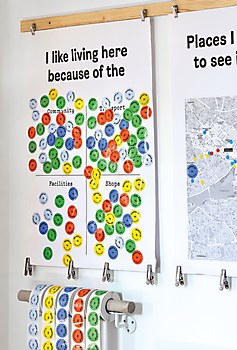

In another actionable project, Fieldwork Facility created the Museum of Us, a platform for residents of London’s Old Kent Road area commissioned by the Southwark London Borough Council. The platform addressed community consultation, a legally required period for new UK architectural developments where the real estate companies must ensure their work responds to the needs of the community. In collaboration with London-based architectural and real estate–planning forum New London Architecture, Fieldwork Facility developed a campaign, exhibition, project space and program of events to convey that the Museum of Us was for local residents to add their opinions on recent developments and join events and workshops.

Fieldwork Facility’s posters, featuring photographs of locals by photographer Suki Dhanda and vibrant sticker-like dots, invited residents to

a refurbished shop where they could engage in conversations and share their opinions on the future of their neighborhood. “Our design language for the Museum of Us stemmed from this idea that one of the easiest ways to participate is by voting with a sticker, so we designed the program’s branding to feel like a celebration of stickers,” Howie says. “Elsewhere, this sticker idea carried over from the brand and communications into the exhibition design, too. We made display panels that felt like big sticker sheets had been made up, powder-coated to match real stickers used in the exhibition that people [could] vote with.”

It should come as no surprise that, with the three projects I’ve mentioned, Howie’s favorite projects with Fieldwork Facility are the ones that outright engage the public. While he might eschew specialization with his design firm, he does offer these three statements to categorize its work: “We reimagine and rewire places to create a public good. We create brands that are ready to thrive in tomorrow’s world. We invent and define platforms that invite a brighter future closer.” That relentless optimism Howie strives for ensures that Fieldwork Facility will keep transforming communities through design and bring them into that exceptional future. ca